Flick through any of the plethora of general interest channels on satellite and cable television and it won’t take long before you come across a documentary about the rise of Hitler, the Battle of Britain or the blitz. Understandably, the majority of our coverage regarding World War II is heavily weighted towards our own national interest and participation, leaving a large portion of equally as important events uncovered. This is certainly the case regarding the conflict on the Eastern front of Germany which is often regarded as merely an inconvenient distraction to the Nazi party (despite it accounting for over 26 million Soviet deaths).

Thursday, 26 May 2011

Tuesday, 24 May 2011

Heartbeats ★★★☆☆

French-Canadian writer-director-star, Xavier Dolan took the festival circuit by storm back in 2009 with I Killed My Mother. This promising debut quickly stapled his name onto every ‘up-and-coming’ director list around. Heartbeats was completed only a year later and critics now will get to decide whether Dolan is indeed the new ‘great white hope’ many proclaimed him to be, or simply another case of a young man who peaked to early.

Heartbeats depicts the tale of a doomed ménage à trois. Our two central protagonist are Francis (Xavier), a stylish gay man who longs to be loved, and Marie (Monia Chokri), a young girl with a delightful shabby chic style that aspires for that perfect partner with whom to overcome the sexual trappings of a relationship and find the perfect ‘spoon’ fit, which she believes is the secret to a long and meaningful partnership.

We join these two close friends who, whilst enjoying a leisurely lunch with mutual acquaintances, both land eyes on the same man, Nicolas (Niels Schneider), a young boy fresh from the country who’s newly arrived in town. As soon as they both coyly declare they have no interest in this fresh faced Adonis, we know what we’re in store for....

Heartbeats depicts the tale of a doomed ménage à trois. Our two central protagonist are Francis (Xavier), a stylish gay man who longs to be loved, and Marie (Monia Chokri), a young girl with a delightful shabby chic style that aspires for that perfect partner with whom to overcome the sexual trappings of a relationship and find the perfect ‘spoon’ fit, which she believes is the secret to a long and meaningful partnership.

We join these two close friends who, whilst enjoying a leisurely lunch with mutual acquaintances, both land eyes on the same man, Nicolas (Niels Schneider), a young boy fresh from the country who’s newly arrived in town. As soon as they both coyly declare they have no interest in this fresh faced Adonis, we know what we’re in store for....

A series of intimate rendezvous leads the trio into an

uncontrollable love triangle as both Francis and Marie fight for the attentions

of this new object of their desires. The pair both eventually fall deeper into

a pit of obsession and fantasy, and as their feeling escalate, it becomes clear

that it won’t just be their emotions that are put to the test but also the

resolve of their cast-iron friendship. Indeed, Nicolas become something of a

poisoned chalice, and what at first starts out as a story of the poetic

craziness of falling in love soon becomes more a study of the humiliation of

rejection and the heartfelt pain that loneliness can bring…

The issue of a love triangle is nothing new in cinematic

terms. Recent French cinema has already delighted us with Les Chansons d’Amour

(a delightful love letter to the musicals of Jacques Demy) and Dreamers (a

flawed but no less enjoyable celebration of classic cinema). Heartbeats

attempts to shine a different light on the topic by focusing on the destructive

element it can inevitably have on the ones it hurts. Whilst it may sound an

attractive prospect, a relationship shared three ways generally only heightens

the percentage of chance that someone will be cast aside when the novelty

expires and the usual traumas and tribulations of a real relationship start to

raise their heads. Director Xavier Dolan’s has decided not to shy away from

this fact and has instead wallowed within it. However, its many flaws along the

way prevent it from being the masterpiece he has set out to make.

The first place to start with this critique would be the

seemingly redundant frame narrative that Dolan has wrapped around the story –

where individuals give their views on sexual encounters and try to shed their

own light on the reasons relationships so often fail. These ‘talking heads’

segments seem like little more than an obvious attempt to fill in the gaps of

what is quite a superficial movie, which hasn’t the depth to cover the

magnitude of these emotional issues. Unfortunately, Dolan’s attempts to cover all

too many bases fails and what actually transpires is nothing more than an

irritatingly, self-centered side piece that not only acts to disrupt the film’s

pace but also never seems to gel with the incidents that surround it.

Following on with this theme of self-centered storytelling

is the obvious issue of Xavier Dolan himself. There is always a hint of

arrogance in the air with any director who decides to cast himself in the

leading role. Numerous times throughout the film peripheral characters refer to

his character as “cute” or “handsome,” and there comes a point when this

glorification of one’s self becomes hard to stomach. The decision to take the

role of a very self detrimental character also screams of nothing more than

preposterous attention seeking and greatly influences the overall enjoyment of

a film which ultimately feels like nothing more than a man singlehandedly

crying out to be noticed. Dolan is quite obviously a handsome man with a lot of

underused talent, so his need to act like this becomes infuriating for the less

‘glamorous’ members of the audience who no doubt aren’t even close to having

the looks or artistic talent to rival this seemingly unfulfilled young man. He

clearly has the opportunity to do great things if only he focused more on his

art than what others think of him.

This try-hard attitude is also apparent within other

elements of the film. The soundtrack, for example, is filled with classic

‘calling card’ bands and blares out at an uncomfortable decibel level, forcing

you to pay attention regardless of whether or not the gratuitous over use of

strobe lighting has already directed your attention away to other less

objectionable sights in the cinema – like perhaps the plush velour of the seat

in front or the inviting gleam of the exit sign. To be fair, though, there are

moments where Dolan does manage to successfully navigate this fine line between

high art and obnoxious pomposity (like a glorious use of a classical score to

heighten the film’s more intimate moments).

This is certainly a film which falls into the category of

style over substance, yet the stylish tricks performed, which don’t come across

as overly gratuitous or farcical, all point to a talented filmmaker with an

obvious eye for a shot and an ability to make the most from a modest cast list.

He may wear his influences firmly on his sleeve (whether it be the slow motion

imitation of In The Mood For Love or the obvious comparisons with Jules et Jim)

and this ability to re-create such style whilst maintaining the film’s own

unique direction is worthy of praise. Unfortunately, these flashes of

brilliance only illuminate the numerous flaws of a director who’s clearly

underperforming.

Heartbeats is a film you’ll desperately want to fall in love

with. Yet Dolan’s attempts to mix high art with deadpan humour in a framework

of emotional devastation falls just short, resulting in a somewhat cluttered,

arrogant mess of a film that may well excite and titillate at first, but will

ultimately leave you disappointed by the end – but like all immature crushes,

given time, it’ll become completely forgettable.

Thursday, 19 May 2011

Love Like Poison ★★★☆☆

Coming of age dramas are as synonymous with French cinema as socio-economic films about class divides are to the independent British film industry. This long running love affair began with The 400 Blows, which sparked not only this genre but a revolution across cinemas around Europe, all the way to more contemporary fare such as the lesser heralded but no less poignant; Blame it on Fidel and Water Lilies. It’s no doubt a well trodden path but for good reason as the subject matter has a mysterious ability to continually charm and engage us as an audience. The scenery may change and as generations fly by the rules may become more liberal but despite the constantly evolving transitions of these rites of passage, the confusion and awkwardness of the progression from childhood to adulthood is something that is ever present and instantly recognisable – indeed it’s something that regardless of sex, race or beliefs we can all identify with in one way or another....

When 14-year-old Anna (Clara Augarde) returns home from her

Catholic boarding school for the summer holidays, she discovers that things

aren’t quite as they should be in her quiet rural household. Her father has

finally flown the family nest, leaving her distraught mother seeking

consolation through her faith; specifically from the village’s young priest,

Father Francois. Perhaps to escape these external dilemmas, or in an attempt to

fill the recent father shaped void in her life, Anna, in no less a charitable

action, decides to take on the responsibility of caring for her ill

grandfather, who may well be at death’s door but certainly isn’t lacking in

youthful verve or spirit.

As the long summer days unwind, she begins to submerge

herself in a series of romantic rendezvous with neighbouring altar boy Pierre.

This exploration of her budding sexuality only exacerbates her already

turbulent inner struggle dealing with adolescence. Combined with the fact that

her conformation is just days away, she is torn between advancing herself

sexually or spiritually…

The most striking element of this film is undoubtedly the

exceptional performance coaxed out of acting debutant Clara Augarde. This young

girl has been thrown straight into the deep end with this unconventionally

honest role, yet she comes across ever the professional, looking like a well

honed actress with the world at her feet. She appears in almost every shot and,

perhaps down to her closeness in age with the character, she deals with these

awkward pubescent moments with a quality of natural performance rarely seen.

Many teenage girls would justifiably run a mile if asked to perform some of the

film’s incredibly personal and revealing scenes, yet Augarde commendably takes

it in her stride, impressively shifting between the fragility of a child and

the staunch defiance of a newly empowered woman.

This slow and subtle drama certainly aims to be more than

just a mere coming of age tale, instead evolving into a deceptively slight

portrait of natural human behaviour. Most crucially, showcasing our constant

struggle against carnal urges through the self-imposed chains we use to

restrain ourselves, whether it be through laws, religion or just a sense of

common decency. Despite the heavy focus on young Anna, there is definitely a

wealth of other well rounded characters from which the film derives its

narrative.

As well as Anna’s fragile family dynamic, there’s the rather

interesting sub plot involving the young girl’s mother and the priest. Both

seem to acknowledge that there’s a mutually reciprocated attraction, but, due

to their strong religious values, it is never consummated. Indeed, it is this

portrayal of various troubled relationships, by director Katell Quillévéré that

separates Love Like Poison from similar, yet more singularly focused tales of

such youthful trials. In particular, the divisive use of Pierre, the young boy

Anna becomes transfixed with, is of great interest – the similarities with

himself and Anna’s father turns an otherwise sweet (if not slightly awkward and

fumbling) relationship into a haunting depiction of how fatally flawed we are

as human beings, continually repeating the mistakes of our forefathers.

As to be expected, one of the central themes explored here

is the bond between mother and daughter. Not only do they share the wealth of

the screen time, but theirs is also the most complex and engaging of all the

relationships on show here. With one discovering her new found womanhood and

the other’s biological clock counting down rapidly, their mirroring physical

changes makes for an emotionally charged series of encounters.

Music, too, plays a huge role in Quillevere’s first feature

film. Its title literally translates as ‘The Violent Poison’ and come from a

Serge Gainsborough song that focuses on the tension love can create, pulling

apart families. It’s perhaps the use of traditional folk music, all sang by

women, that is the most interesting, acting as a comforting collection of

‘words of wisdom’ to reassure us that Anna’s problems are as old as time.

Anna’s grandfather adds some much needed light relief;

however, it’s a role which is underdeveloped and could have a lot more to offer

than just the jovial offhand remarks we are privy to. His atheist, and

light-hearted beliefs could have lead to a viewpoint on the issues of love and

sexual desires unhindered by religious constraints that would have helped

engage the film to a wider audience – who may otherwise find the heavy use of

Catholicism a little too suffocating and alien to relate with.

There is also a disappointing lack of dramatic conflict

considering the heightened anxiety that broods behind each interaction within

this quaint Breton parish. Whilst this slow burning build up creates an

interesting and initially gripping level of tension, the lack of any final

emotive explosion or conclusive scene of redemption leaves an unremarkable

taste, which does little to separate it from recent films such as Jessica

Hausner’s Lourdes; another beautifully shot film steeped in questionable

religious traditions, which equally takes an impartial viewpoint after

initially promising to do much more with the subject matter.

This empathetic vision of adolescence, whilst a competent

piece of searching filmmaking, ultimately lacks enough confrontation to make

its detached mood stay with you any further than the end credits. Whilst this

quintessentially introspective coming of age drama certainly holds its own, it

could have doubtlessly made more of the existential aroma or religion it

shrouds itself in. More is the pity as Quillevere and Augarde are, based on the

flashes of brilliance shown in this their debut feature, certainly both names

to watch out for.

Tracker ★★☆☆☆

At the turn of the 20th century, in an unnamed costal town in New Zealand, a larger than life, rough round the edges, ex-Boer war guerrilla, Arjan( Ray Winstone) clearly stands out amongst the crowds of returning soldiers and immigrants. He’s arrived to build himself a new life after being left with next to nothing but is greeted with a less than hospitable welcome. It would appear he’s arrived with more than just physical baggage and his fierce reputation as a colourful and violent man has also made the long journey with him to this distant arm of the British Empire. However, despite this initial stumbling block, his renowned tracking skills soon find him under the employ of British commanding officer Major Carlisle.

Friday, 13 May 2011

Julia's Eyes ★★★☆☆

The most terrifying and effective psychological horrors don’t rely on shocking scenes of gratuitous violence to traumatize their viewers but rather more subtle techniques to get under their skin. Mixing a bleak and dissonant score with a collection of dark and claustrophobic shots can create an atmosphere of foreboding doom, cultivating a level of heightened fear in the auditorium that becomes almost palpable. Indeed it’s often what you don’t see that’s the scariest, leaving your imagination to conjure up your greatest fears, constructing something far more horrific and personal than any film director could possibly conceive. With this in mind surely a Guillermo Del Toro produced thriller with a focal character who suffers from a degenerative eye disorder (gradually rendering her blind as the movie progresses) must have all the ingredients needed to freak-out even the most hardened fan’s of the genre?

Biutiful ★★★★☆

Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s stunning Oscar nominated debut, Amores Perros, undoubtedly helped raise the profile of Central and South American filmmakers worldwide. Whilst many of his contemporaries moved on to more mainstream projects, Inarritu staunchly stuck to his guns, creating films in his own distinctive style that continued to captivate audiences with their characteristic mix of thought provoking narrative, erratic plot devices and visually hypnotizing scenes. However, the beautifully puzzling and strikingly honest realism in his film’s has often been credited to his partnership with former writing collaborator, Guillermo Arriaga. Biutiful is Inarritu’s first feature without him onboard but will this sudden departure from non-linear storytelling detract from his unique and evocative style or leave it more vulnerable to criticism from those who say his work is a classic example of ‘Style over substance’?

Friday, 6 May 2011

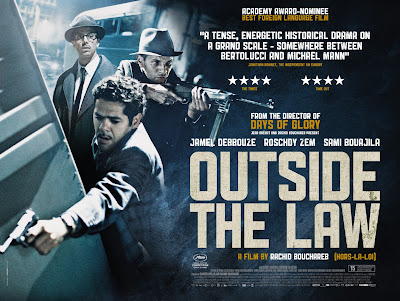

Outside The Law ★★☆☆☆

Outside the Law is the second part of Rachide Bouchareb’s planned trilogy charting Algeria’s long and troubled history under French control (the first being his hugely successful Days of Glory). Yet where his previous effort won him acclaim for its tribute to the neglected Algerians who fought to free France and it’s colonies from the plight of fascism which spread across Europe during World War II, his recent effort has garnered much controversy with protestors at its Cannes premier and numerous French cinemas refusing to show it. This is deemed to be down to the films pro Algerian standing and Frances much complicated and still unresolved history regarding its occupation of the African country.

Flying Monsters 3D ★★★☆☆

There has always been an argument that film’s need to be seen on the ‘big screen’ to truly be appreciated, the same could equally be said for nature documentaries, especially concerning those made by David Attenborough a man whose name is globally synonymous with the genre and deserves every square foot given to him by the good people at the BFI IMAX.

Tuesday, 3 May 2011

Deep End ★★★★☆

In 2008, Jerzy Skolimowski returned from a self imposed, seventeen year absence from directing (reportedly to concentrate on his true passion – painting) with his much lauded come back, Four Nights With Anna. Last month he followed up that success with Essential Killing, described by many as his most painterly presented film yet. It has also gained high praise for its lead performance by Vincent Gallo – an actor renowned for being difficult to direct. To coincide with its release, and to celebrate this underrated director’s return from the cinematic wilderness, the good people of the BFI have gracefully decided to restore one of Skolimowski’s most revered and respected pieces from the 1970s – his previously unattainable cult hit about adolescent passion, Deep End.

Mike (John Moulder-Brown) is fresh out of school and still

very much wet behind the ears when he takes up his first job as a bathroom

attendant at a rundown swimming baths in West London. It is here he meets Susan

(Jane Asher) and it doesn’t take long before this attractive young redhead,

with her breathtaking beauty and teasing demeanour, becomes the object of

Mike’s obsessions.

The revelation that not only is Susan engaged, but also

having a lurid affair with Mike’s former P.E teacher, is like an arrow through

the young boy’s heart. Yet, whilst many of us would begrudgingly surrender

defeat, and bottle away our carnal desires, it only strengthens Mike’s resolve

to destroy Susan’s wedding plans and expose her adulterous nature in an attempt

to make her his own.

What starts as an innocent crush soon manifests itself as

something much worse and as Mike’s determination over takes his common sense,

the lines of decency and morality begin to diminish and there seems to be no

stopping the momentum of this treacherous fixation. He quickly falls steadfast

into a series of events which look on course to end in tears…

Released during the height of the French New Wave and the

hangover effect of the swinging ‘60s, Skolimowski’s British made tale of

obsession and desire is a delightful mix of the type of work that both Godard

and Truffaut were creating at the time but with a distinctive underlying

English sensibility. This delightful mix of the desolate beauty of London with

the sort of subtle nuances and loving attention given to character detail which

we’ve come to love from the nouvelle vague truly separates Deep End from a lot

of the cinema being produced here at that time. Our unconscious manner for

comparing and creating films to the modern Hollywood mould often results in

nothing more than a continued conveyor belt of drab, uninspired and, most

importantly, unoriginal films. Deep End is a wonderful example of how drawing

influence from other cultures can have a strikingly profound effect on a movie

without making it completely inaccessible to a wider audience.

John Moulder-Brown does a wonderful job with the character

of Mike. Starting off as a picture of innocence, he seamlessly crosses the

boundaries of right and wrong without succumbing to a melodramatic about turn,

making his performance all the more haunting. Jane Asher, with her ‘60s chic

style and piercing stare needs little direction in portraying a temptress; she

could quite easily have stood mute on screen for the film’s entirety and still

have passed as competent within the role. However, she doesn’t and you’ll soon

find yourself sympathising with Mike’s infatuation for her, although perhaps

not to the same fatal degree. A fleeting cameo by Doris Dors is also due a

mention, as a mildly camp carry-on-esque turn as a steamy, bath house patron.

She undoubtedly opens Mike’s eyes to the seedy underside of adulthood and

singlehandedly removes the last shreds of his innocence. It’s a pivotal

performance that could so easily have undone Skolimowski’s hard work at

creating a story of passion without hysteria, yet instead adds some light

relief to an otherwise subtly sinister depiction of sexual fixation.

Deep End also garnished its cult status thanks to its

eclectic soundtrack by Krautrock heroes Can and the guilty pleasure that is Cat

Stevens. The fact that the undiscerning ear could easily miss this whilst

watching is in itself a compliment to the film’s production. It’s ever present,

yet its unobtrusive nature makes it a perfect companion, never distracting you

from the story that unfolds in front of your eyes or the dialogue that wisps

along so elegantly.

The only criticism to be levied towards Deep End is the

fairly obvious symbolic clues it leaves along the way that perhaps make the

ending (which in itself has left many viewers wanting) not as poignant as

perhaps it could have been. The final third lacks the ambiguity this film’s

rich build up deserves, like those sitcoms which leave you cringing at what’s

to follow. Skolimowski dark observation of Mike’s perilous descent into a

maddening addiction for Susan, however palpable it may seem, surpasses being

unbearable and instead leaves only the question of how this obvious fate will

manifest itself into its logical conclusion.

Regarding the film’s digital transfer, the hard working

restoration team at the BFI have yet again managed to do justice to another

lost classic. The film may have aged noticeably, and the age old problem of

poor 1970s dubbing is still apparent, but with regard to the lovingly recreated

film print, you’d be hard pressed to criticise what is at heart a marvellous

achievement for a film which deserves such a beautiful return to the big

screen.

With Deep End, Skolimowski may have dived head first into

the deepest part of the male psyche, but by no means does he sink under the

pressure. Instead, he has created a film which manages to propel past its self

imposed obstacles, which could otherwise have left it stranded in a sea of

teenage confusion.

Rachel ★★☆☆☆

This film was screened at the 2011 London Palestine Film Festival.On March 16th 2003, Rachel Corrie, a young American woman volunteering as a peaceful activist in the southern Gaza strip town of Rafah, was crushed by an Israeli army bulldozer in an act many witnesses claim was deliberate, but, predictably, the local police and government deemed an accident. Through varied accounts from fellow activists, local towns folk and members of the IDF (Israeli Defense Force), documentary maker Simone Bitton attempts to show but never tell the events that led to this disastrous incident, leaving us, the viewer to take what evidence there is and come to our own conclusion from her hushed, solemn investigation.

Daniel Deronda ★★★☆☆

Fresh from director Tom Hooper’s recent Oscar triumph, comes this re-release of his 2002 BAFTA winning, BBC mini-series, Daniel Deronda. Despite the obvious attempts to cash-in on the recent success of The King’s Speech there are many who proclaim this Victorian period drama to be very much on a par with the hugely popular, Pride and Prejudice and deserving of much wider acclaim that it had previously received.

Read More...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)